Dateline – Playa Conchal, Costa Rica

All good things must come to an end and this vacation does tomorrow. I’m up in the morning beginning the twelve hour process of returning to Birmingham by way of the Liberia airport. As far as I know, there are no hitches but with the government shutdown affecting air traffic control, all bets are off once I hit the United States. I suppose if I get stuck in Atlanta, I can rent a car or something.

I didn’t write last night as I really didn’t have anything to say. (A pre-dinner cocktail and two glasses of wine with dinner probably didn’t help). Yesterday and today both followed the established pattern. Sleep in (which usually means up about 7:30 local time). Leisurely breakfast. Beach and pool time (with sunburn to prove it) until midafternoon with something for lunch in the middle. Clouds and rains arrive around 3 PM so repair to the room for reading, writing, and nap. Venture forth around 7 for dinner and another glass of wine. Back around 8 for more reading, writing and Netflix and eventually drop off for some uninterrupted sleep.

I have been thinking about partisan politics and healthcare policy for the last week or so after reading some rather ridiculous claims from both sides of the aisle regarding the shut down and the role health care is playing in the whole thing. For those of you solely interested in travelogue, you can stop reading now. For those of you interested in my historical analysis of health care policy, hang on. It’s a long one. It might take you more than one sitting. It certainly took me more than one to write it.

The current imbroglio in DC which has led to a governmental shut down has, at its heart, a dispute over health care. The party which currently holds power, the Republicans keeps attempting to frame it as if the Democrats are entirely to blame and that what the Democrats are trying to do is guarantee free health care to undocumented residents. This is a gross misreading of the situation (as anyone with even a modicum of intelligence and inquisitiveness soon discovers). Therefore, the Republicans are using every tool in their box to try and force this narrative through to public consciousness. This requires multiple violations of what is known as The Hatch Act (federal employees using their jobs for partisan purpose). This law has been on the books since the 1930s and has been adhered to for nearly a century by both parties until recent days. The problem is that enforcement is dependent on the White House Office of Special Counsel and that office is under a management that has no interest in stopping the promotion of Republican alternative facts.

Therefore, I thought it might be interesting to look back at the last century or so of national legislation that has impacted our health care system and look and see what roles our two governing parties have played, either for or against. It’s not as clear cut as one might think and these issues have been used over and over in political gamesmanship, usually to the detriment of the health of Americans. While most of the world has left the design and construction of their health care systems to clinicians, public health experts, and systems analysts, here in the US we have generally relied upon politicians, industrialists, and bankers. That’s why our system costs so much more and delivers so much less than any other comparable first world country.

The first movements towards health insurance and a federal role in handling the costs of health care emerged shortly after the turn of the 20th century during the progressive era. It was one of many ideas considered by Teddy Roosevelt (R) but it wasn’t considered as important as other concerns, so nothing happened on a governmental level. The burgeoning labor movement picked it up in the years leading up to World War I with the American Association of Labor Legislation drafting a model bill in 1915 and beginning to lobby at the federal level with the Woodrow Wilson (D) administration. The American Medical Association joined in and there was some traction until 1917 when political conditions changed. First, life insurance companies lobbied against the bill, feeling that the availability of health insurance might eat into their profits. Second, more conservative state medical societies challenged the national leadership over issues of federal control over health care decisions. And lastly, and most importantly, the US entered World War I. Germany, the enemy, had a robust social insurance system that included health care. The idea of the US government providing health benefits became entangled with the World War I era Red Scare with the Prussian Menace of socialist programs being inconsistent with American values. Le plus ca change le plus de meme chose.

During the roaring 20s, health care was not an important part of the American economy. The average American family spent more on cosmetics per year than on health. Most health care happened in the home with mom or granny providing the nursing care. Physicians were generally engaged in primary care and lived and worked in a community of people whom they came to know well. Hospitals existed, but for certain specialized services and were, in general, owned by not-for-profit groups with specific charitable mission. Hospitals were places most people avoided but could provide surgical services, quarantine services (mental health, tuberculosis), care for those without intact family structures, and training for the next generation of providers.

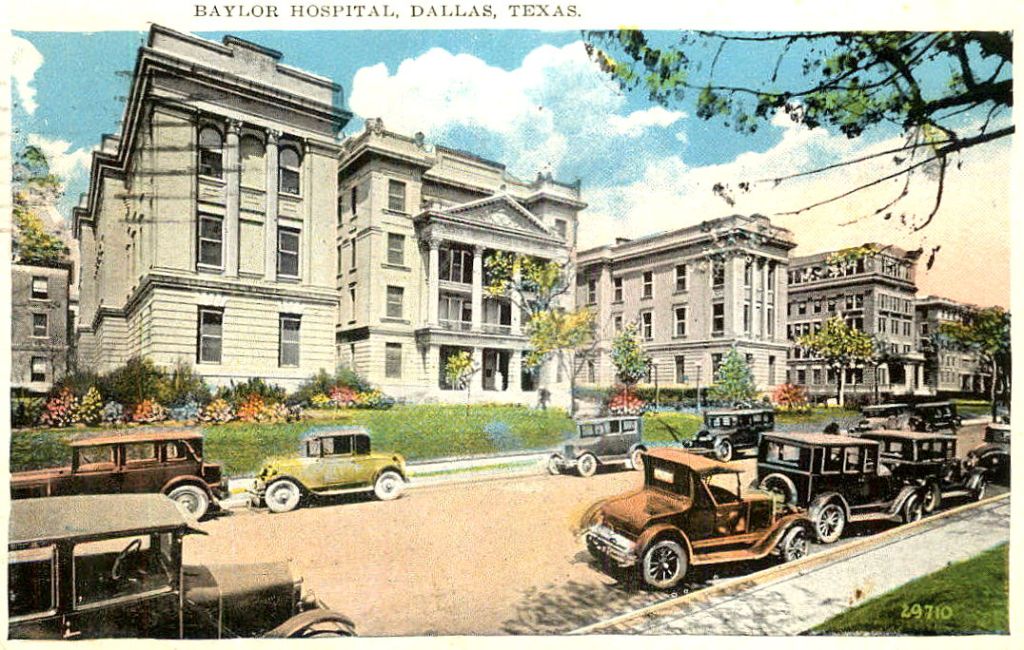

In 1929, with the economy careening towards The Great Depression, health costs were starting to rise. Justin Ford Kimball, the then vice-president for health facilities at Baylor University in Dallas Texas, came up with a novel idea. His institution had just built a new hospital and was having difficulties filling the beds. The middle-class workers of the area were becoming concerned with rising costs and being able to afford health care. Kimball struck a deal with the Dallas teachers union. If union members would pay 50 cents a month to Baylor, they would become entitled for up to 21 days of free care at Baylor’s hospital should they need it and the first American health insurance plan was born. Ten years later, in 1939, after a number of other such arrangements began to spring up, an association of plans felt to be providing value and service were given status by the American Hospital Association and given the symbol of Blue Cross plans. At roughly the same time, the loggers and miners of the Pacific Northwest, who had high rates of occupational injuries and illnesses, had employers who recognized the need for keeping a healthy workforce and began contracting with local providers. These plans adopted the name Blue Shield. The two groups formally merged in 1982.

At the same time as the emergence of the Blues, the federal government was starting to get interested again in health care and its costs. When Franklin Roosevelt (D) proposed the Social Security Act in 1935, one of the benefits that he wanted to see included was a national health insurance plan. However, as the AMA had by this point taken the position that any government intervention in medical practice was ‘socialized medicine’ and to be opposed at all costs, it was decided to leave this particular piece of the legislation out as its inclusion might endanger the passage of the bill as a whole. There was another attempt at a national health insurance bill in 1939 which would have given federal block grants to the states to set up their own programs, but FDR never really got behind it, and it withered on the vine.

In the early 1940s, a new bill, known as the Wagner- Murray-Dingell bill, which would have established compulsory national health insurance was drafted and named after the three Democratic senators who pushed it. It was reintroduced every year from 1944-1957 under presidents Roosevelt (D), Truman (D) and Eisenhower (R). Roosevelt was preoccupied with World War II. After the war, the cause of national health insurance was championed by Harry Truman through both of his terms. He had to contend with a Republican led legislature who refused to consider the bill. In addition, the anti-communist sentiment of the McCarthy era burst forth and the AMA, in particular, was happy to taint national health insurance with the ‘socialist’ or ‘communist’ label making it impossible to move forward.

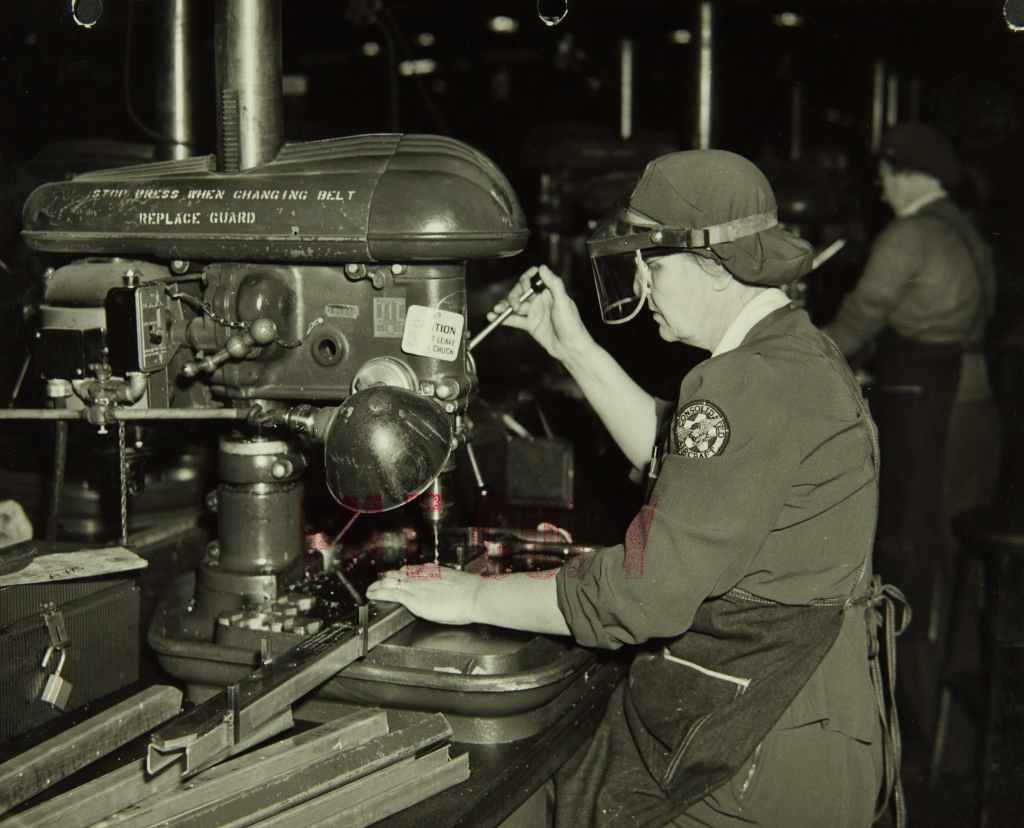

At this same time, a historical accident was changing the playing field. During World War II, when many of the able-bodied men were out of the country fighting, the heavy industrialists charged with making war materials hired women to build the aircraft and ships and munitions necessary for the war effort. It didn’t take long for the titans of industry to figure out that women had domestic duties outside of the assembly line. If they or their children became ill, they would miss shifts and slow production. Henry J. Kaiser, of Kaiser steel, pioneered the idea of corporate responsibility for the health of its workers in order to maximize production providing company subsidized health care to employees and their families. A few years later, when the men returned from overseas and went back to work, heavy industry found itself with a dilemma. Wage and price control legislation, left over from The Great Depression, was still in effect. Higher wages could not be used as an incentive for hiring so, instead, benefits were placed on the table including health insurance, leading to the development of our employment-based health care system which took root nowhere else. The government encouraged this by making these benefits tax exempt on both the employer and employee side via various tax reforms introduced between 1943 and 1954.

In the 1950s, a combination of factors collided leading to a more urgent need for the federal government to take a hand in health insurance. The explosion of medical technology and understanding fueled by the war effort, the widespread introduction of antibiotics, and the growing reverence of American culture for physicians and other providers were leading to a switch in the centering of health away from the home to the hospital and driving the idea of American exceptionalism in medicine. (A reputation deserved at that time). This in turn, was leading to a significant increase in the cost of health care for families, especially those who were excluded from the employer-based model of health insurance due to age or disability. As hospitals were still, for the most part, owned and operated by not-for-profit entities of charitable mission, they were starting to feel a financial squeeze from unreimbursed care from people demanding the new treatments American medicine could provide but having no real means to pay the bill and trusting in the charitable mission of the hospital to assist with that.

It was President Eisenhower ( R) who recognized the significant issues regarding aging and employer-based health insurance and he led the first White House Conference on Aging at the end of his term in 1961. After the assassination of his successor, President Kennedy (D), Lyndon Johnson (D) was able to get various health and welfare programs through congress in late 1964 and early 1965 as part of his Great Society plans which aimed to eliminate poverty. Medicare was signed into law as an amendment to the Social Security Act in July of 1965. An additional amendment to the Social Security Act established Medicaid, health insurance for the impoverished. While Medicare is a true national health insurance program, Medicaid is an optional program for which the federal government provides funds to states to set up their own systems and it varies in each state. In fact, it took nearly twenty years for all states to sign on. Arizona was the last state to do so in 1982.

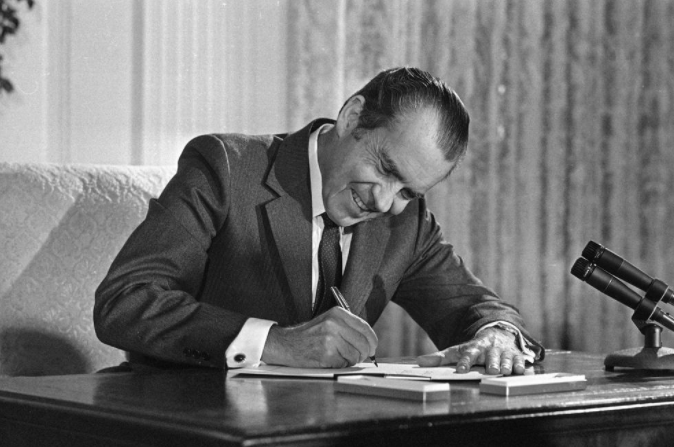

The creation of Medicare and Medicaid allowed for more and more money to enter the health care system and, by the 1970s, several things began to happen. First, with new treatments and technologies plus the need to build new facilities for these and to train providers in their appropriate use, medical costs began to increase and rise at a rapid pace. Second, the titans of finance began to notice the amount of money entering the health care sector of the economy and began to form corporate entities to harness and take advantage of these dollars. Health care was pretty much a not-for-profit enterprise until 1973 when Richard Nixon ( R) signed the federal HMO act, championed by senator Teddy Kennedy ( D) as a way to curb medical inflation. It allowed for private enterprise to set up health maintenance organizations (which could be for profit) and cleared away bureaucratic red tape in order for them to compete with the traditional health insurance offered by the Blues. These new HMOs began to buy up pieces of the health system and organize them into networks of care and began a process of acquisition and conglomeration that continues. Their first attempts to control costs were to reduce access through gatekeeper mechanisms which were resoundingly hated by most of the population. Their next attempts, by creating networks and reducing choice in that way, as they were more stealth, worked better.

Throughout the 1980s, the competition between access, quality, and cost dominated health issues. Medicare had a major reform in 1983 with the implementation of diagnosis-related groups and batch payments to hospitals signed into law by President Reagan ( R). But there were bright spots. At the time, hospitals, becoming more and more concerned about the bottom line due to corporate influence, were becoming more and more involved in a practice known as patient dumping. Refusing to treat or actively transferring patients with emergency conditions from private to public hospitals with many cases reported of horrific outcomes due to delays in care. Congress, with a Republican controlled senate and Democratic controlled house passed the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act and it was signed by President Reagan ( R). This law states that no hospital which receives federal funds may refuse to treat a patient presenting with an active emergency condition until that patient has stabilized. It does not allow for any discrimination based on any status including citizenship or documentation. (This is the free medical care to illegal aliens that the Republicans are currently ranting about – notice who signed it into law).

Reagan waded into health care one more time at the end of his political career. There is some speculation that he was somewhat chagrined by his mishandling of the HIV epidemic in its early years and was trying to make amends through EMTALA and, in 1988, the Medicare Catastrophic Care Act. The intent of this piece of legislation was to protect seniors on Medicare from medical bankruptcy. It had become relatively common knowledge, by this time, that seniors were spending a greater portion of their incomes and assets on health care than they had prior to the introduction of Medicare in 1965. The reason for this was that elders were now recovering from acute illness and living longer and developing chronic illnesses requiring supportive care that was not part of the purview of Medicare such as assistance with basic activities of living at home. The legislation was designed to make Medicare into a stop loss program. All Medicare beneficiaries would have a deductible but once that was met, if their health costs went beyond that, Medicare would step in and keep them from having to pay more. In order to raise the additional dollars for Medicare to cover these expenses for the few who would need them each year, congress raised taxes, but solely on the Medicare beneficiaries who would benefit from the program. The elder lobby went ballistic and flexed its muscles with significant strength for the first time. Their bone of contention was that this should not be a cost placed solely on the shoulders of elders but should be borne by all of society. The backlash was so severe that congress repealed the measure before it went into effect.

The battles over health care have continued pretty much unabated in more recent decades. In 1993, newly sworn in President Clinton (D) was determined to tackle the increasingly dysfunctional American health care system.. He had campaigned heavily on health care reform and was determined to make sure that all Americans could access quality health care at a reasonable price. He appointed his wife, Hillary, to lead a task force to create legislation which would accomplish these goals. She gathered all of the best minds she could in closed door meetings in DC and prepared a more than thousand-page bill. The lack of transparency and the time it took for her to put her plan together helped seal its doom. The health insurance industry, which would have no longer needed to exist had the plan gone forward, sponsored a very effective television ad campaign known as the Harry and Louise ads to turn public sentiment against the plan. The Heritage Foundation and Bill Kristol rallied the conservative movement against the plan and, perhaps more importantly, against the first lady. When Clinton gave his major address to congress on health care in September of 1993 urging the passage of his bill, it was already too late. Key congress folk, who had been kept out of the closed-door meetings were lukewarm in their support. The bill never got a hearing in its original form. Some watered-down compromises were floated but got no traction. The American public, leery of Democrat controlled big government fueled by this battle, voted in the modern movement conservatives led by Newt Gingrich in the midterms of 1994 and that was that.

The close fought election of 2000, eventually decided by the supreme court, ushered in a new Republican administration under President Bush ( R). His first term was dominated by the tragedy of 9/11 and his misguided invasion of Iraq in response. Later, after the 2002 midterms, when the Republicans held the presidency and both houses of congress for the first time in nearly fifty years, attention turned to domestic matters, especially as congress had been getting an earful regarding medical inflation, especially drug prices from their constituents. Seniors, in particular, were being hard hit as Medicare had no drug benefit. This was not due to neglect but rather to the philosophy and design of the program.

When Medicare was enacted in 1965, the chief issue was that elderly were excluded from hospital and other care for illnesses for which modern medicine was developing effective treatments. Medicare was created to allow elders access to the health care system for treatment of acute illness so that they could be improved and go back to productive lives. Medicare was relatively unconcerned with chronic illness. A much smaller percentage of the elder population at that time was disabled by chronic illness. Acute illness carried them off before they could settle into years of debility. Daily medication is not, in general, necessary with acute illness. That requires short courses or medications administered in health care facilities – items covered by Medicare. Taking pills daily for years on end at home was not something that anyone was concerned about in 1965. This prompted congress to pass the Medicare Modernization act in 2003, signed into law by President Bush ( R) in December of that year. The MMA has two chief sections: Medicare C which formalized HMO plans offered by private insurance companies as Medicare Advantage which seniors could elect to replace their traditional Medicare. These plans offer all Standard Medicare benefits and often a little lagniappe like a gym membership but are profit driven. They make their profits by restricting benefits through restricting participants to certain networks of providers (not necessary in traditional Medicare), prior authorization procedures, and strict scrutiny looking for reasons to deny benefits. These plans have been a goldmine for private health insurance but not such a bargain for the tax payer as the cost is roughly 27% more per capita than traditional Medicare. The other is Medicare D which is a drug benefit plan. It is best known for its infamous donut hole – it stops paying benefits once a certain amount is paid and then picks up again on the other side for ‘catastrophic’ cases and resets every year. There were other clauses inserted to benefit the insurance and pharmaceutical industries such as one preventing the government from negotiating price reductions with drug companies and buying in bulk for Medicare purposes. Ultimately the law, still in effect, became a very convenient mechanism to transfer wealth from the government to the corporate side of the health care industry and helped accelerate the costs of the system.

When the Democrats regained control of the White House again with the election of Barack Obama in 2008, there was significant pressure on the administration to do something to improve access to the health care system due to the high number of uninsured priced out of the system and the continued skyrocketing costs within the system. The Obama team knew all too well about the failures of previous years such as the debacle of the Medicare Catastrophic Care act, the collapse of the Clinton health plan, and the dubious financial issues embedded in the Medicare Modernization Act. The Obama team, knowing that they did not have the votes for true single payer or national health insurance, instead looked at proposals made by Republicans in their attempts to head off such major changes. The Heritage Foundation, a right wing think tank, started drafting what they called market-based health care reforms built around insurance exchanges and an individual mandate that all must have insurance but that there should be various means of obtaining it. These ideas were put into practice in the state of Massachusetts under Governor Mitt Romney ( R) in 2006 and proved fairly successful.

Obama, with a Democratic majority in congress, signed the Affordable Care Act into law in 2010, although most of its provisions did not come into play for a few more years. Even though the legislation was built on Republican philosophy and models, the Republican party did not want to give Obama a legislative win and swung into action to denigrate the law from its inception. Several Supreme court cases knocked out some of its underpinnings such as the individual mandate and the requirement that states participate through Medicaid but what remained worked relatively well. The Republicans continue to threaten to throw the whole thing out in order to tarnish Obama’s legacy, but they have nothing with which to replace it.

For the insurance exchanges to work and for premiums to remain affordable, there must be federal subsidies in place to help regulate the marketplace. Those subsidies were set to expire after a set period of time, based on the assumptions of universal participation which never happened thanks to the supreme court rulings on the Republican lawsuits. They end at the end of this calendar year. If those subsidies are not extended, people who get their insurance through the exchanges will see their premiums skyrocket to unaffordable levels. This is what the Democrats are holding out for currently. They want the Republicans to agree to continue those subsidies and aren’t interested in coming back to the table as long as they refuse. President Trump ( R) and his administration and Mike Johnson and the Republican house caucus are refusing and mischaracterizing the whole fight as being about Democrats wanting to give free healthcare to the undocumented. This is simply not true. The only care undocumented people are entitled to is emergency care under EMTALA as we as a country, forty years ago, thought it was a bad thing for desperately ill people to be turned away when life saving care was available.

Now you know far more about partisan politics and American health care policy than you ever wanted to. What have I learned after cogitating on all of this and spending a few hours writing it down? 1. None of what’s going on is new. Our great grandparents were having the same arguments and our great grandchildren are likely to do the same. 2. The incremental and accidental ways in which we change our health system don’t work very well. Perhaps it’s time to try something more drastic. 3. If Ronald Reagan were still around, he’d be drummed out of the modern Republican party as a RINO.